Beyond Behavior Cloning: The Future of Autonomous Driving Through Closed-Loop Training

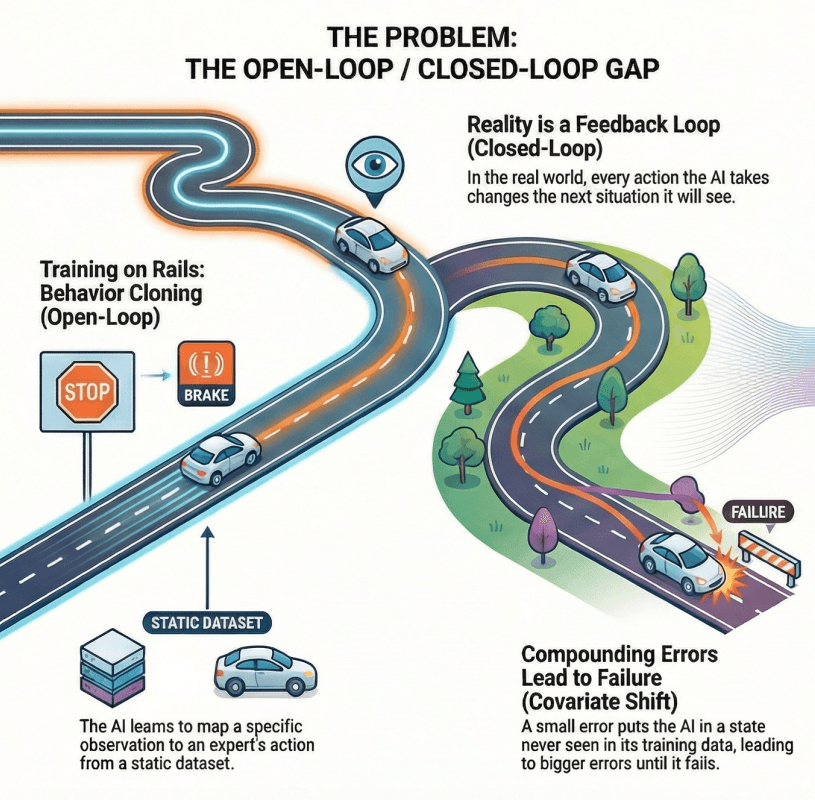

The autonomous vehicle industry stands at a critical juncture. While behavior cloning has enabled impressive demonstrations of end-to-end driving systems, a fundamental gap threatens to limit further progress: policies trained on static demonstrations must operate in a dynamic, interactive world where every action shapes future observations. This article explores how closed-loop training techniques are reshaping the path toward full autonomy.

Part I: Understanding the Problem

The Promise and Peril of Behavior Cloning (Learning by Watching, promise of Imitation)

How exact do you teach an AI to drive? The simplest idea should be the best one: let it watch a really good human driver. But will this simple approach work in the real world?

Short answer: No, the AI is never gonna be a perfect 1-to-1 copy of the human driver. Small differences will always exist and grow over time.

But it turns out that this straightforward approach—known as behavior cloning—suffers from a critical flaw.

Behavior cloning operates on an elegant but flawed premise: train a neural network (policy) to predict expert actions given observations, treating each moment (network's input) as independent from the next. Mathematically, this involves minimizing a loss function over expert demonstrations, where the policy learns to map sensor inputs directly to control outputs. The approach has proven remarkably effective for initial development, leveraging the massive datasets of human driving logs collected by AV companies.

However, reality imposes a harsh constraint. During deployment, any deviation from the expert trajectory, however slight, pushes the vehicle into states it never encountered during training. Without experience recovering from these novel situations, errors compound quadratically over time. A steering miscalculation of just a few degrees becomes a lane departure within seconds, then a collision within moments. Deviation from the expert trajectory distribution is usually caused by unmodelled dynamics e.g. the during supervised training the model does not experience the feedback loop of its own actions affecting future observations. Unmodelled delays in actuation, sensor noise, and environmental variability are the main contributing factors.

The Open-Loop to Closed-Loop Gap: Five Critical Failures

The mismatch between open-loop training and closed-loop deployment manifests in five distinct failure modes, each representing a fundamental challenge for autonomous systems.

Covariate Shift and Compounding Errors:

The state distribution seen by the policy deviates from the distribution in the training data.

The most severe issue occurs when the policy encounters states outside its training distribution. As the policy is rolled out in closed-loop operation, small deviations from the expert amplify over time, pushing the system into increasingly unfamiliar regions of the state space. Eventually, the policy finds itself so far from anything it has seen that recovery becomes impossible.

Causal Confusion: Behavior cloning suffers from learning spurious correlations rather than true causal relationships. A classic example: the policy learns to brake when surrounding vehicles slow down, rather than identifying the red traffic light that caused those vehicles to brake. In training data where both signals correlate perfectly, this distinction seems academic. In deployment, when the policy must make split-second decisions in ambiguous scenarios, it becomes catastrophic.

Unmodeled Interactivity: Autonomous driving is fundamentally interactive—the ego vehicle's behavior influences other road users, which in turn alters the ego vehicle's future observations. Behavior cloning, trained solely on passive observation of expert demonstrations, does not model this bidirectional influence. Consequently, policies may learn behaviors that appear reasonable in isolation but provoke undesirable reactions from other agents in practice.

Downstream Control and Vehicle Dynamics: Predicted trajectories are never executed perfectly. They must obey vehicle dynamics and typically pass through downstream controllers that introduce latency, noise, and actuation limits. Since behavior cloning policies are not exposed to these effects during training, they often fail to appropriately account for the gap between planned and realized trajectories.

Long-Tail Events: Rare but critical scenarios pose a persistent challenge. Behavior cloning is vulnerable because these events are underrepresented in expert data and contribute little to the training loss. Without corrective feedback during training, policies often cannot adapt to or recover from rare situations—precisely the scenarios that determine whether a system can operate without human supervision.

Critical Insight: Open-loop training assumes independent samples, but closed-loop deployment creates temporal dependencies where today's actions determine tomorrow's observations. This mismatch isn't a minor technical detail—it's a fundamental epistemological challenge.

Part II: The Solution Framework

How Do We Teach an AI to Recover From Its Own Mistakes?

You don’t only need to know how to follow the expert, but also how to go back on track when you deviate from it.

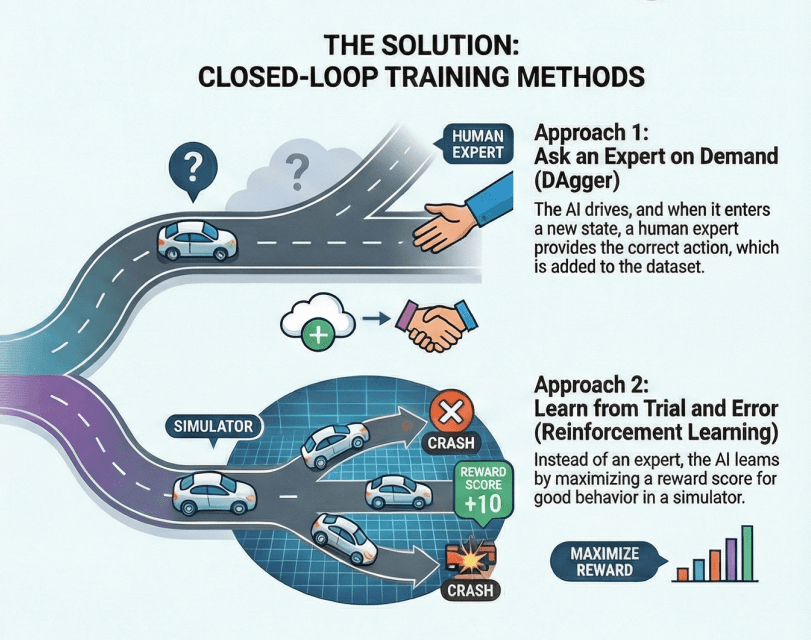

The short answer is: instead of just using thousands of hours of expert driving data, give a proper in-car driving lesson, with a human instructor ready to correct the mistakes of the student. There are multiple ways to do this, and they all fall under the umbrella of closed-loop training (Practice, Mistake, Correct, Repeat).

Closed-Loop Training: Experiencing Consequences During Learning

Closed-loop training directly addresses these limitations by exposing policies to the consequences of their own actions during the training phase. Rather than treating each observation-action pair as independent, closed-loop methods generate complete rollouts where each action influences future observations through environment dynamics. This allows the policy to experience compounding errors, practice recovery maneuvers, and develop robust strategies for novel situations.

The core principle is deceptively simple: generate additional relevant experience that results from iteratively executing the policy, ensure this experience is realistic enough to avoid sim-to-real failure modes, then update the policy with an objective aligned to desirable driving performance. However, achieving this in practice requires navigating a complex design space with fundamental trade-offs.

The Three-Axis Design Space

Modern closed-loop training approaches can be understood through three interdependent design axes, each presenting distinct trade-offs that shape the entire training pipeline:

| Axis | Question | Options |

|---|---|---|

| Action Generation | How are ego actions generated? | Passive perturbation → Guided rollouts → On-policy rollouts |

| Environment Response | How is the environment simulated? | Game engines → Neural reconstruction → Generative models |

| Training Objective | What is the learning signal? | Imitation Learning → Hybrid IL+RL → Reinforcement Learning |

⚠️ Design Coupling Warning: These axes are deeply coupled—choices in one constrain options in others.

Part III: Design Axis 1 — Generating Actions

In standard behavior cloning, we train on expert data: the expert drove, we recorded observations and actions, and the AI learns to predict those actions from those observations. But this only teaches the AI what to do in states the expert visited—not what to do when the AI makes a mistake and ends up somewhere else.

Closed-loop training fixes this by generating training data from states the AI visits. The first design question is: who drives the car during training data generation?

This choice creates a spectrum:

- Expert drives with perturbations: We replay expert logs but inject small artificial errors. Safe, efficient, but the errors are generic—not tailored to the AI's actual weaknesses.

- AI drives freely: The AI controls the car in simulation. We capture its real failure modes, but it's expensive (must regenerate data constantly) and early on produces mostly useless crash data.

- Hybrid approaches: The AI drives with guardrails, or we filter/curate its rollouts to keep only informative data.

The choice of who drives determines which states get visited, and therefore what the AI can learn to handle. Let's examine each approach.

Approach 1: Passive Perturbation

The idea: Take recorded expert driving and add small artificial errors—shift the car 10cm left, delay braking by 0.1 seconds, rotate the heading by 2°. Now you have a "perturbed state" that's slightly off from where the expert was.

How we get the correct action: Since we only perturbed slightly, we can still use the expert's original action as the training target. The assumption is: "if you're 10cm left of where the expert was, the expert's action is still approximately correct." For small perturbations, this holds reasonably well.

Alternatively, we can query an expert policy (a hand-coded controller or a privileged model with perfect information) to provide the "correct" recovery action from the perturbed state.

Why it's useful: You can generate this data once and reuse it forever. It's fast, reproducible, and you control exactly what scenarios to create.

The problem: These artificial errors might not match the mistakes your AI actually makes. If your AI tends to oversteer in left turns, random perturbations won't specifically target that weakness unless you're lucky.

Approach 2: Active Rollouts (Let the AI Drive)

The idea: Let the current AI policy control the car in simulation. When it oversteers, it experiences the consequences. When it brakes too late, it ends up in a novel state.

How we get the correct action—two options:

Option A: Query an expert (DAgger-style) At each state the AI visits during its rollout, ask an expert "what should I do here?" This expert can be:

- A human driver (expensive, doesn't scale)

- A privileged policy with access to ground-truth (e.g., knows exact positions of all objects, has perfect maps)

- A hand-coded controller (e.g., "steer toward lane center")

The AI then learns to imitate these expert labels from the states it visited, not just states the expert visited. This directly addresses covariate shift.

Option B: Use rewards (Reinforcement Learning) Instead of asking "what's the correct action?", define a reward function:

- +1 for staying in lane

- +10 for reaching the destination

- -100 for collision

- -1 for uncomfortable acceleration

The AI explores through its rollouts, collects rewards, and learns which actions lead to high cumulative reward. No expert labels needed—the AI discovers good behavior through trial and error.

Why it's useful: The AI learns from exactly the mistakes it makes—no coverage gap between training and deployment.

The problem:

- For expert queries: You need an expert that can answer "what should I do?" from any state, including weird ones the expert would never reach

- For RL: You must regenerate data after every training update (expensive!), and early on the AI crashes constantly, giving you mostly useless data with -100 collision rewards

- Both face a chicken-and-egg problem: needs good experience to improve, but needs to be good to generate good experience

Approach 3: The Middle Ground — Hybrid Methods

Most practical systems use clever compromises. Here are the three main strategies:

Strategy A: Guided Rollouts (CAT-K)

Let the AI explore, but with guardrails. The AI proposes several possible actions, and we pick the one that keeps it closest to what the expert did.

Simple version: AI says "I could steer left, straight, or right." System checks which option keeps the car closest to the expert's recorded path, executes that one, then trains the AI to prefer that choice.

This way, the AI reveals its tendencies (maybe it wants to oversteer) but we prevent catastrophic drift. The AI learns which of its instincts are problematic.

🔧Technical Deep-Dive: How CAT-K Works▶

The CAT-K (Closest Among Top-K) Algorithm:

- At each timestep, sample K candidate actions from the policy (e.g., K=10 steering/acceleration combinations)

- Simulate one step forward for each candidate

- Select the action yielding the state closest to the expert's recorded position at that timestep

- Train the policy to predict this selected action

The distance metric is typically:

Key insight: We compare to where the expert was, not what the expert would do. This only requires recorded logs, not an oracle that can answer "what should I do from this weird state?"

The K parameter: K=1 is pure on-policy (AI's top choice). K→∞ approaches pure expert tracking. K=5-20 is typical.

Limitation: Only works on recorded scenarios—can't use for novel situations.

Strategy B: Stale Policy Rollouts

Instead of regenerating data after every training update, reuse data from a few updates ago. The intuition: if the AI oversteered by 3° yesterday and oversteers by 2.8° today, yesterday's data is still mostly relevant.

The savings: Instead of running simulation after every gradient update, regenerate every 10-100 updates. That's 90-99% less simulation cost.

This works well in early training when improvements are small. It fails when the AI suddenly "gets it" and changes behavior dramatically.

🔧Technical Deep-Dive: Rollout Generation Pipeline▶

What "generating rollouts" means:

- Take policy at iteration

- Run it in simulation from various starting states

- Record (observation, action, next_observation, reward) sequences

- Train the policy on this data

Standard on-policy: Regenerate after every update. Expensive but fresh.

Stale rollouts:

- Generate with

- Train for N iterations:

- Only then regenerate with

The correction signal:

- Imitation learning: Query expert for correct action at each visited state

- Reinforcement learning: Use collected rewards (+1 lane keeping, -100 collision)

When it works: Early training, smooth optimization, incremental fine-tuning

When it fails: Breakthrough moments, mode collapse recovery, late-stage training

Strategy C: Quality Filtering

Let the AI drive freely, generate lots of rollouts, then curate the best ones for training. Throw away the useless crashes, keep the informative failures.

Filtering strategies:

- Crash filtering: Remove instant crashes (< 0.5s). No useful signal there.

- Duration weighting: A 10-second drive before failure is more informative than a 1-second crash.

- Diversity selection: Ten different failure modes beat ten copies of the same crash.

- Challenge targeting: Keep rollouts that reach hard scenarios before failing.

🔧Technical Deep-Dive: Tree Search Enhancement▶

Using MCTS to improve policy outputs:

- Policy proposes initial trajectory

- Tree search explores variations using a value function

- Best trajectory becomes the training target

- Policy learns to produce search-quality outputs directly

This creates a policy improvement operator: policy + search > policy alone. Training on search-improved targets gradually transfers this improvement into the policy itself.

The goal: eventually deploy the policy without expensive online search, because it has internalized the search process.

Summary: The Action Generation Spectrum

Off-Policy Benefits

- ✓Computationally efficient

- ✓Can reuse data across runs

- ✓Stays near valid demonstrations

On-Policy Benefits

- ✓Captures actual policy failures

- ✓Directly addresses covariate shift

- ✓Learns from real mistakes

Industry Evidence: Why On-Policy Matters (comma.ai, 2025)

When evaluating driving policies on simulated driving tests (lane keeping, lane changes), policies trained purely off-policy failed despite achieving better offline trajectory accuracy metrics. Meanwhile, policies trained on-policy—using either reprojective simulation or learned world models—passed these tests and were successfully deployed in comma.ai's openpilot ADAS. The lesson: optimizing for offline metrics can be misleading. What matters is how the policy performs when it must handle the consequences of its own actions.

Part IV: Design Axis 2 — Generating Environment Responses

Once we decide how to generate actions, we face an equally challenging question: how does the world respond? This second design axis concerns the simulation environment that transforms policy actions into subsequent observations—and it represents perhaps the most technically demanding aspect of the entire closed-loop training pipeline.

Game Engines (CARLA, etc.)

Explicit 3D geometry with hand-crafted assets. Perfect controllability and ground truth, but synthetic appearance.

⚠ Perceptual gap with real world; doesn't scale to diverse environments

Neural Reconstruction (NeRF, 3DGS)

Learn photorealistic scenes from real driving footage. Anchored to actual sensor data.

⚠ Can only interpolate near recorded trajectories; degrades outside validity corridor

Generative Video Models

Synthesize 2D frames directly via diffusion/autoregressive models. Can generate rare events on demand.

⚠ Lacks 3D grounding; spatial/temporal consistency issues; hard to compute rewards

Latent World Models

Operate in learned feature space, bypassing pixel rendering entirely. Orders of magnitude faster.

⚠ Coupled to policy architecture; bounded by representation quality

The Trend: Moving from explicit geometry toward learned representations, trading controllability for realism and scale.

The Core Challenge: High-Fidelity Sensor Simulation

The challenge stems from a fundamental asymmetry in end-to-end driving. These policies consume raw sensory inputs—camera images, LiDAR point clouds, radar returns—and must learn to extract the driving-relevant information themselves. This is precisely what makes them powerful: they can potentially discover features that human engineers would never think to encode. But it also means the simulation environment cannot cheat by providing clean bounding boxes and lane graphs. It must render photorealistic sensor observations that match the distribution the policy will encounter in the real world.

This requirement creates a demanding technical bar. If simulated images look subtly different from real images—wrong lighting, missing reflections, unrealistic textures—the policy may learn to exploit these differences rather than the underlying driving task. The sim-to-real gap becomes not just an evaluation problem but a training failure mode. A policy that performs brilliantly in simulation may fail immediately when confronted with the visual complexity of actual roads.

Traditional Game Engine Simulation

Game engines like CARLA have long served as the foundation for closed-loop research, and for good reason. These systems leverage decades of computer graphics development to render 3D scenes from explicit geometric representations. Every object has a defined position, every surface has material properties, and the rendering pipeline produces consistent, controllable outputs. Researchers can construct specific scenarios—a pedestrian stepping into traffic, a vehicle running a red light—and replay them deterministically.

This controllability proves invaluable for algorithm development and ablation studies. When something goes wrong, you can examine exactly what the policy saw and trace the failure to specific perceptual or decision-making errors. Ground truth is perfect by construction.

However, the perceptual gap between rendered and real-world images remains substantial. Real-world driving involves countless visual phenomena that game engines struggle to capture: the way sunlight scatters through windshields, the subtle reflections on wet asphalt, the visual texture of vegetation, the appearance of motion blur at speed. Synthetic environments feel synthetic, and neural networks are remarkably good at detecting these differences. More critically, constructing detailed 3D assets for diverse driving environments doesn't scale—each new city, each new road type, each new weather condition requires extensive manual modeling that becomes prohibitively expensive as coverage requirements grow.

Neural Reconstruction: Photorealism Anchored to Reality

Neural reconstruction techniques—particularly Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) and 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS)—represent a paradigm shift in how we think about simulation. Rather than building virtual worlds from hand-crafted assets, these methods learn to reconstruct photorealistic scenes directly from multi-view camera footage collected during real-world driving.

The core idea is elegant: given images from multiple viewpoints, learn a continuous 3D representation that can render novel views through differentiable volumetric rendering. Drive through an intersection once with calibrated cameras, and you obtain a neural representation that can synthesize what the intersection looks like from any nearby viewpoint—including viewpoints the vehicle never actually occupied.

Systems like AlpaSim demonstrate that this approach can achieve remarkable visual fidelity while remaining anchored to real-world appearance. Because the reconstruction is learned from actual sensor data, it inherently captures the full complexity of real-world perception: the way light bounces off different materials, the subtle shadows cast by overhead structures, the visual texture of road surfaces after rain. No manual asset creation is required, and the resulting images are difficult to distinguish from photographs.

The trade-off manifests in limited generalization. Neural reconstructions are, at their core, sophisticated interpolation—they can render views between and around the training viewpoints, but they cannot genuinely extrapolate to regions of space they have never observed. A policy that turns left where the recording turned right quickly encounters degraded rendering quality as it moves outside the "validity corridor" where the reconstruction remains reliable. This constraint necessitates the guided rollout strategies discussed earlier, keeping the ego vehicle close enough to recorded trajectories that the environment can render convincing observations.

Reprojective Simulation: A Lightweight Alternative

Before committing to full neural reconstruction or generative world models, there's a simpler technique worth understanding: reprojective simulation (comma.ai, 2025). The idea is elegant—use depth maps to reproject real recorded images to new viewpoints, creating the illusion that the vehicle took a slightly different path.

How it works: Given a recorded frame and its estimated depth map, we can geometrically "warp" the image to show what the scene would look like from a nearby viewpoint. If the policy steers 2° left of where the recording drove, we reproject the original image to that new pose.

This approach has been deployed in production systems like comma.ai's openpilot, demonstrating that even simple geometric techniques can enable meaningful closed-loop training. The key advantages:

- Anchored to reality: The source images are real photographs, preserving authentic lighting and textures

- Computationally lightweight: No neural network inference required—just geometric transforms

- Immediate deployment: Can be implemented with existing depth estimation models

However, reprojective simulation has fundamental limitations that constrain its applicability:

- Static scene assumption: The technique cannot model how dynamic objects (other vehicles, pedestrians) would respond to the ego vehicle's different trajectory

- Lighting artifacts: Reprojecting images can create visible seams and artifacts, especially under challenging lighting conditions

- Limited deviation range: As the ego vehicle moves further from the recorded trajectory, occlusion effects become severe—you can't see behind objects that were never visible in the original recording

- Shortcut learning risk: Policies may learn to exploit artifacts in the reprojected images rather than the underlying driving task

For production systems, the practical approach is often to use reprojective simulation for modest deviations while falling back to more sophisticated techniques (learned world models, generative video) for larger explorations. The comma.ai team, for instance, developed both reprojective and world model simulators in parallel, finding that both enabled successful on-policy training but with different trade-off profiles.

Generative Video Models: Flexibility at the Cost of Structure

The newest frontier abandons the 3D-to-2D rendering pipeline entirely. Generative video models and interactive world models synthesize 2D frames directly, using diffusion or autoregressive architectures trained on massive video datasets. Rather than reconstructing a specific scene and rendering novel views within it, these systems learn to generate plausible driving videos conditioned on actions and initial frames.

The potential is transformative. Models like GAIA-2 and Cosmos-Drive can evolve scenes beyond the constraints of any recorded log, creating rare events on demand that would require millions of driving miles to encounter naturally. Want to train on pedestrians darting into traffic? Construction zones with confusing signage? Emergency vehicles approaching from behind? Generative models can synthesize these scenarios without waiting for them to occur in data collection. Recent work with TeraSim shows particular promise, conditioning generation on StreetView imagery and external traffic models to achieve both visual fidelity and scenario diversity.

Yet generative approaches introduce challenges that stem from their very flexibility. Without explicit 3D grounding, spatial and temporal consistency becomes difficult to enforce. Vehicles may subtly change shape between frames. Objects may pass through each other in ways that violate physics. The generated world is plausible frame-by-frame but may not represent a coherent physical environment.

More fundamentally, the lack of structured scene representations complicates reward computation and evaluation. Reinforcement learning typically requires knowing when collisions occur, when lane boundaries are crossed, when traffic rules are violated. These quantities are trivial to compute in a game engine with explicit geometry but become estimation problems in a purely generative world. How do you measure collision risk when object boundaries exist only implicitly in pixel space?

The field is actively exploring hybrid approaches that attempt to combine geometric grounding with generative flexibility. Diffusion models can refine neural reconstructions, adding visual diversity while preserving geometric structure. Generative enhancement can improve game engine outputs, making synthetic images more realistic while retaining the underlying ground truth. These methods represent a promising direction, though the optimal balance between controllability and realism remains an open question.

Latent World Models: Abstraction for Efficiency

A conceptually distinct alternative sidesteps the sensor simulation problem entirely. Latent world models operate not in pixel space but in the learned feature space of the policy itself. Rather than predicting what the next camera frame will look like, they predict what the next latent representation will be—the internal features the policy extracts from observations.

This abstraction offers profound efficiency gains. Consider what actually matters for driving decisions: the positions and velocities of nearby vehicles, the geometry of the road ahead, the state of traffic signals. A photorealistic render contains millions of pixels encoding these few dozen relevant variables along with countless irrelevant details—the texture of trees, the color of buildings, the exact shade of the sky. Latent world models can potentially capture the driving-relevant dynamics while ignoring the visual complexity, reducing computational requirements by orders of magnitude.

Early applications show genuine promise, particularly for trajectory optimization and constraining rollouts toward expert-like states. The models can simulate thousands of rollouts in the time required for a single photorealistic render, enabling planning algorithms that would be computationally prohibitive in pixel space.

However, latent models exhibit tight coupling with the policy architecture that creates practical challenges. The "world" they model is defined by the policy's feature extractor—when that feature extractor changes during training, the world model becomes stale and must be retrained. More fundamentally, the predictive quality of a latent world model is bounded by the informativeness of the latent representation itself. If the policy's features fail to capture some aspect of the driving environment, the world model cannot predict it. This means latent models struggle with precisely the long-tail scenarios that challenge the policy—a concerning limitation since these are often the scenarios where closed-loop training provides the greatest benefit.

Traffic Agent Simulation: The Interactive Element

Beyond visual rendering lies an equally critical challenge: simulating the behavior of other road users. Driving is fundamentally interactive. The ego vehicle's decisions influence other agents, who respond in ways that shape the ego vehicle's future observations and decision points. A simulation that ignores this bidirectional influence produces policies unprepared for the reactive world they will encounter.

The design space for traffic simulation presents its own spectrum of fidelity-efficiency trade-offs. Log-replay offers perfect fidelity for interactions between other agents—they behave exactly as recorded humans behaved—but completely ignores the ego vehicle's influence. The simulated vehicles follow their recorded trajectories regardless of what the ego does, which means the policy never learns how its actions affect others. Rule-based models like the Intelligent Driver Model (IDM) provide reactivity: simulated vehicles brake when the ego cuts them off, accelerate when gaps open. But hand-crafted rules struggle to capture the full complexity of human driving behavior, particularly in dense urban scenarios where social dynamics and cultural norms influence behavior.

Learned traffic models trained on real-world driving data represent the most flexible approach, with recent advances leveraging next-token prediction architectures and closed-loop fine-tuning to enhance behavioral realism. These models can capture the statistical patterns of human driving—how aggressively drivers merge, how much following distance they maintain, how they respond to unexpected maneuvers—in ways that rule-based systems cannot.

The critical challenge, regardless of approach, is preventing the policy from exploiting unrealistic traffic behaviors. If simulated vehicles always yield when the ego asserts itself, the policy learns that assertion always works. If simulated vehicles never make mistakes, the policy never learns to handle the mistakes real drivers make constantly. Deploying such a policy among human drivers—who sometimes don't yield, sometimes make errors, sometimes behave irrationally—can produce catastrophic failures. This makes robust, realistic traffic simulation not merely desirable but essential for closed-loop training that transfers to the real world.

Part V: Design Axis 3 — Defining Training Objectives

The third design axis concerns what signal drives learning. Three main paradigms exist, each with distinct trade-offs:

| Approach | Signal | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed-Loop Imitation | Expert demos | Human-like, data-efficient, stable | Limited to expert states, labeling challenge |

| Hybrid IL + RL | Demos + Rewards | Best of both, industry standard | Complex to tune, requires both signals |

| Reinforcement Learning | Reward function | Can surpass expert, defined everywhere | Reward design hard, sample inefficient |

Common hybrid strategies include: IL pre-train + RL fine-tune, imitation-based rewards (deviation penalties), teacher-student schemes (privileged RL expert), and preference learning (DPO variants).

Closed-Loop Imitation Learning: The Expert Label Problem

Closed-loop imitation learning extends the imitation paradigm to handle policy-induced states. The central challenge is straightforward yet profound: expert demonstrations only define desirable behavior along recorded trajectories, but closed-loop rollouts inevitably venture into novel states. How should the system behave when it finds itself somewhere the expert never visited?

The Expert Label Problem: In closed-loop training, the AI drives and makes mistakes, ending up in states the human expert never visited. But we need to tell the AI "here's what you should have done" to correct it. How do we get these labels for states that don't exist in our expert data?

There are three main approaches to solving this problem, each with different trade-offs:

| Approach | How it gets labels | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAgger | Query expert on-demand | True expert behavior | Expensive, doesn't scale |

| Recovery Heuristics | Use simple controllers | Fast, always available | Not human-like driving |

| Latent World Models | Avoid labels entirely—optimize in latent space | Scalable, no expert needed | Requires accurate world model |

Let's examine each approach:

Approach 1: On-Demand Expert Querying (DAgger)

The classical answer comes from DAgger (Dataset Aggregation), which queries an expert on-demand to provide corrective demonstrations for novel states. In theory, this approach elegantly solves covariate shift by ensuring the expert is "defined" wherever the policy goes, transforming quadratic error growth into near-linear regret.

The core loop is simple: Train → Execute → Query Expert → Aggregate Data → Repeat

In practice, on-demand human experts don't scale—the cost and latency of repeatedly interrupting human drivers proves prohibitive. Modern implementations instead use privileged expert policies with access to ground-truth maps and object states. These "expert models" can be queried efficiently during simulation, providing consistent supervision across the entire state space.

Approach 2: Recovery Heuristics and Guided Rollouts

When expert queries prove impractical, recovery heuristics offer a simpler alternative. Geometric controllers can guide the vehicle back toward lane center, PID controllers can maintain appropriate following distance, and trajectory optimization can target expert states as terminal conditions.

Guided rollouts extend this concept by biasing action selection toward states that remain closer to fixed expert trajectories. The Closest Among Top-K strategy samples multiple actions from the policy at each step and executes the one yielding a future state closest to the expert. This balances on-policy exploration with continued validity of expert supervision.

Approach 3: Latent Model-Based Imitation (World Models)

Perhaps the most elegant solution to the expert labeling problem sidesteps explicit action labels entirely. Instead of asking "what action should I take?", we ask "what future state should I reach?"—and we answer this question in a learned latent space.

The key enabling technology here is the world model—a neural network that learns to simulate the environment. By training a world model on diverse driving data, we can generate realistic future scenarios without needing a human expert to label them. The policy learns by imagining possible futures in this simulated world and optimizing for good outcomes, all happening inside the model's learned representation. This is what makes closed-loop training possible without constant expert intervention.

🌍Deep Dive: World Models for Closed-Loop Training▶

What is a World Model?

A world model is a neural network that learns to predict what happens next given the current state and an action. Think of it as the AI's internal mental simulator.

Simple Definition: A world model answers: "If I'm in situation X and I do action Y, what situation will I end up in?"

For driving:

- Input: Current scene representation + proposed action (steering, throttle)

- Output: Predicted next scene representation

The Key Insight: Operating in Latent Space

Here's the crucial detail that makes this practical: the world model doesn't predict raw sensor data (images, LiDAR). Instead, it operates in a compressed latent space—a learned low-dimensional representation.

Why this matters: A camera image has millions of pixels. A latent representation might have only 256-1024 numbers. The world model predicts in this small space, not pixel space.

The Three Components

| Component | Input | Output | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encoder | Raw sensors (camera, LiDAR) | Latent vector z | Compress observation to essentials |

| World Model | Latent z_t + action a_t | Next latent ẑ_{t+1} | Predict future in latent space |

| Policy | Latent z_t | Action a_t | Decide what to do |

Addressing the Key Question: How Can You Roll Out Without Sensor Inputs?

This is the critical insight that's often confusing. Let me be very explicit:

During imagination, the world model never sees real sensor data after the first frame.

Here's how it works:

The world model predicts latent→latent, not pixels→pixels.

Once you have from encoding the real initial observation, everything else is prediction:

- — predicted latent, not real sensor data

- — prediction from prediction

- And so on...

The encoder is only used once per trajectory (to get the starting point). After that, we're entirely in "imagination land."

Why Does This Work?

The latent space is designed to capture everything needed for driving decisions:

- Where am I on the road?

- Where are other vehicles?

- What's the road geometry ahead?

- What's my velocity and heading?

The world model learns: "Given this compressed state + this action → what's the next compressed state?"

It doesn't need to know what color the sky is or the exact texture of the road. It just needs to track the driving-relevant dynamics.

Training the World Model

Before we can use imagination, we need to train the world model to make accurate predictions. This uses real sensor data:

Step 1: Collect real driving sequences with recorded actions

Step 2: Encode all frames

Step 3: Train world model to predict correctly

The world model learns to match its predictions to what actually happened.

Training the Policy with Imagination

Now we can train the policy without running the real simulator:

Step 1: Take an expert trajectory and encode it

Step 2: Let the policy imagine from the same start Starting from (same initial state):

- Policy outputs:

- World model predicts:

- Policy outputs:

- World model predicts:

- Continue for T steps...

Step 3: Compare imagined vs expert trajectories

Why Gradients Can Flow Backward

This is the "differentiable simulator" concept:

Traditional simulators (CARLA, etc.):

- Black box: action in → state out

- Cannot compute: "How should I change to improve the state at step 10?"

- No gradients flow through

World model (neural network):

- Fully differentiable chain:

- Can compute: via backpropagation

- Gradients flow from final loss, through all predictions, back to policy

Concrete example: If the policy's imagined trajectory drifts left by step 10, the gradient tells us: "The steering at step 1 was 0.5° too aggressive—reduce it."

Computational Advantage

| Method | What it needs | Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Real simulation | Physics engine, rendering, sensors | ~100 steps/sec |

| World model | Matrix multiplications | ~100,000 steps/sec |

The world model is ~1000× faster because:

- No physics computation

- No image rendering

- No sensor simulation

- Just neural network forward passes in low-dimensional space

The Critical Limitation: Model Accuracy

The policy learns to reach states that look good according to the world model. If the world model is wrong, the policy learns the wrong thing.

Failure mode example:

- Real physics: jerking the wheel causes skidding

- Bad world model: predicts smooth lane change

- Policy learns: "aggressive steering is fine"

- Real deployment: crash

This is why world model fidelity is critical. The model must accurately capture:

- Vehicle dynamics (acceleration, turning radius, tire grip)

- How the scene evolves (other vehicles moving, traffic lights changing)

- What information the policy actually needs

The fundamental tradeoff: World models are fast but approximate. Real simulators are slow but accurate. Most practical systems use world models for rapid iteration, then validate in higher-fidelity simulation.

Future-Anchored World Models: Creating Recovery Pressure

A particularly elegant innovation in world model design is future anchoring (comma.ai, 2025)—conditioning the world model not just on the current state but also on a desired future state. This seemingly simple modification has profound implications for policy learning.

The key insight: By showing the world model where you want to end up (e.g., staying centered in the lane 3 seconds from now), the generated trajectory naturally curves toward that goal—regardless of the current deviation.

In standard world models, if the policy makes a mistake (drifts left), the world model dutifully predicts what happens next—the car continues drifting left. The policy must learn, through trial and error, that this leads to bad outcomes. Future-anchored world models take a different approach: by conditioning on the "correct" future state (where the expert would be), the model generates rollouts that recover from the current mistake.

This creates what researchers call recovery pressure—the imagined trajectories inherently demonstrate how to get back on track, rather than just how errors compound. The policy learns both "what should I do when things are going well?" and "how do I recover when I've made an error?" in a unified framework.

comma.ai's implementation uses a Diffusion Transformer architecture for their world model, conditioning on future poses to generate video predictions. The plan model then provides ground-truth trajectories that guide the policy toward these anchored futures. This approach has been validated in production, enabling policies trained entirely in simulation to successfully drive in the real world.

Reinforcement Learning: Learning from Consequences

Reinforcement learning offers a conceptually cleaner solution: replace expert demonstrations with a reward function that can be evaluated anywhere. The policy learns through trial and error, receiving direct feedback from the environment and gradually discovering robust strategies. This paradigm naturally handles closed-loop dynamics and can, in principle, surpass human performance in specific scenarios.

The Reward Design Challenge: However, RL introduces formidable practical challenges. Reward design for human-like driving remains notoriously difficult—how do you encode the nuanced balance of safety, efficiency, comfort, assertiveness, and social convention into a scalar signal?

Poor reward specifications lead to reward hacking, where policies exploit unintended loopholes or develop unsafe shortcuts. A policy might drive aggressively to maximize progress, slam on brakes to avoid collision penalties, or discover and exploit bugs in the simulator. Even minor misspecifications in edge cases can cause catastrophic failures.

Sample Efficiency and Computational Demands: The sample inefficiency of RL algorithms demands high-throughput simulation. Prior work in simplified settings used hundreds of millions or even billions of environment steps. For end-to-end policies processing high-dimensional visual inputs, this translates to compute requirements that push the boundaries of current infrastructure.

On-policy methods like PPO require particularly high throughput because simulation sits inside the training loop—every gradient step must wait for freshly generated experience. Achieving training times measured in days rather than months often requires simulation speeds of 10⁴ to 10⁵ steps per second.

Action Representation Challenges: Unlike standard RL domains with simple action spaces, driving policies often predict extended-horizon trajectories. Treating multi-second trajectories as instantaneous actions inflates dimensionality and variance. Tokenized policies that discretize trajectories complicate the mapping to actions. Diffusion-based policies don't directly provide log-probabilities needed for policy gradients. These architectural considerations require specialized RL algorithms that remain underexplored.

Hybrid Approaches: Combining the Best of Both Worlds

The most promising path forward combines elements of both paradigms, trading some dependence on expert demonstrations for improved training efficiency and robustness.

Imitation-Based Rewards: The core problem with pure RL is reward design—how do you write a formula that captures "good driving"? One elegant solution: derive the reward from expert demonstrations.

Instead of manually specifying rewards, we let the expert data define what "good" looks like:

The key insight: We have thousands of hours of expert driving. Instead of using this data to directly tell the AI "do this action," we use it to define "this is what good driving looks like"—then let RL figure out how to achieve it.

There are three main flavors:

| Method | How it works | Reward signal |

|---|---|---|

| Deviation Penalties | Add penalty for straying from expert path | |

| Inverse RL | Learn a reward function where expert is optimal | Learned that explains expert behavior |

| Adversarial (GAIL) | Train discriminator to tell expert vs policy apart | — "fool the discriminator" |

Why this matters: Pure RL needs you to manually define every aspect of good driving (lane keeping: +1, collision: -100, comfort: ???). Imitation-based rewards say: "just look at what humans do—that's the definition of good."

The trade-off: You've shifted the problem from "learn a good policy" to "learn a good reward function." If your reward function doesn't generalize to new situations, neither will your policy. The complexity doesn't disappear—it moves.

Sequential IL and RL: A promising paradigm pre-trains policies with behavior cloning then fine-tunes with reinforcement learning, mirroring the pre-training and alignment stages that transformed large language models. Imitation provides a human-like baseline, while RL improves robustness in challenging scenarios where human demonstrations prove inconsistent or suboptimal.

However, this handoff introduces pitfalls. If the value function (critic) is trained on static data, it often overfits to the behavior policy. When evaluated on closed-loop rollouts it must extrapolate, causing estimation bias that leads to policy divergence. Remedies include conservative critics, advantage filtering, and critic-free RL methods that sidestep value estimation entirely. Direct Preference Optimization and related approaches show particular promise, achieving strong safety metrics through trajectory-level preference alignment.

Teacher-Student Schemes: Another powerful hybrid approach trains a privileged teacher policy using RL on structured world states, then distills this teacher into an end-to-end student using imitation learning. Because the teacher has access to perfect information (exact maps, object states, etc.), it can be trained more efficiently and robustly than an end-to-end policy.

Critically, unlike human experts, the teacher can be queried on-demand for any state encountered during student rollouts, enabling DAgger-style closed-loop imitation without human involvement. Multi-agent self-play for training privileged experts represents a particularly promising direction, with recent results showing strong performance in complex interactive scenarios.

Advantage-Conditioned Policies (RECAP): A particularly elegant approach to hybrid IL+RL emerges from recent robotics research at Physical Intelligence (π*0.6, 2025). The core problem: modern vision-language-action (VLA) models often use flow matching or diffusion-based action heads, which don't provide the log-probabilities required for standard policy gradient methods like PPO. How do you do RL without policy gradients?

The RECAP trick: Instead of computing policy gradients, convert the RL problem into conditional supervised learning. Label each action as "positive" or "negative" based on its advantage, train the policy to generate actions conditioned on this label, then always condition on "positive" at inference.

The key insight is learning contrast—showing the model both successful and failed actions teaches it what to avoid, not just what to imitate. Human interventions during autonomous rollouts are forced to "positive" labels, teaching recovery behaviors. This creates a virtuous cycle where the policy learns from its mistakes while leveraging human corrections.

RECAP has been validated on complex real-world manipulation tasks: laundry folding achieved 2× throughput improvement, espresso making ran continuously for 13 hours, and box assembly reached ~90% success rate. While developed for robotics, the principles transfer directly to autonomous driving—particularly for VLA-based driving policies where standard RL algorithms cannot be applied. See our detailed RECAP article for a deeper exploration of this method.

Part VI: The Coupling Problem

Why These Choices Are Interdependent

A critical insight from recent analysis is that the three design axes cannot be optimized independently. Choices along one axis fundamentally constrain options along the others, creating a complex optimization problem with no universal solution.

Actions ↔ Environment

On-policy rollouts venture far from logs, but neural reconstruction degrades outside validity corridor. Forces guided rollouts.

Actions ↔ Objective

IL objectives only valid near expert trajectories. Fully on-policy generation breaks IL supervision.

Environment ↔ Objective

RL needs structured states for rewards. Generative models lack 3D grounding. Objective constrains viable simulators.

💡 Think holistically: what combination works for YOUR constraints and goals?

Action Generation ↔ Environment Fidelity: Fully on-policy rollouts most effectively address covariate shift, but they may venture far from real-world logs. Neural reconstruction techniques achieve superior visual fidelity near recorded trajectories but degrade rapidly for distant states. This coupling forces practitioners toward guided rollouts or post-hoc filtering—sacrificing some benefits of on-policy exploration to maintain rendering quality.

Training Objective ↔ Action Generation: Imitation-based objectives derived from fixed demonstrations remain reliable only near expert trajectories. Venture too far, and expert labels lose validity. This makes fully on-policy action generation problematic for closed-loop imitation, pushing the field toward off-policy variants or hybrid IL-RL formulations.

Environment Choice ↔ Training Objective: RL requires structured world states to compute handcrafted rewards—collision boundaries, lane constraints, semantic information. Generative video models excel at visual realism and diversity but often lack this structured grounding. The choice of training objective thus influences what simulation environments remain viable.

Data Requirements Across All Axes: RL demands high throughput and low latency, as simulation sits inside the training loop. This favors simulation approaches optimized for speed over fidelity, or necessitates massive parallelization. Imitation learning proves more forgiving, as data generation can be decoupled from policy updates, allowing for higher-fidelity but slower simulation.

These interdependencies mean there is no single "best" approach to closed-loop training—and attempts to optimize each axis independently will likely fail. The optimal design depends critically on available compute resources, deployment constraints, safety requirements, and the specific operational domain. A research lab with limited compute but access to high-quality driving data will make different choices than a well-resourced company prioritizing rapid iteration. A system targeting highway driving can accept simulation trade-offs that would be unacceptable for dense urban deployment.

Practitioners must think holistically, treating the three axes as a single coupled system rather than independent design choices. The question is not "what is the best action generation strategy?" but rather "what combination of action generation, environment simulation, and training objective forms a coherent pipeline given our constraints and goals?" This systems-level thinking distinguishes successful closed-loop training efforts from those that optimize individual components only to discover they don't compose into a working whole.

More Content Coming Soon

This section is currently being refined and reviewed for accuracy. Quality content takes time, and we want to ensure you get the best insights.

Upcoming Topics

Key Works and Citations

The foundational paper establishing DAgger's theoretical bounds, proving that iteratively aggregating datasets from policy rollouts achieves near-linear regret and ensures policies perform well under their own induced distributions.

Organizes the field by action generation, environment response, and training objectives. Explores reward design challenges and the potential of Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models.

Identifies covariate shift as the primary driver of performance degradation in open-loop systems. Details scaling laws for compute and data in embodied AI.

Introduces a specialized video tokenizer to compress high-resolution sensor data into continuous latent spaces. Supports rich conditioning on ego-vehicle actions, weather, and road semantics.

Examines the problem of defining expert behavior when vehicles drift far off trajectory. Proposes hybrid IL+RL objectives as effective industrial solutions.

Covers reward hacking, learning from pairwise comparisons, and interaction-aware control using Stackelberg game modeling.

Demonstrates that on-policy trained policies pass driving tests while off-policy policies fail despite better offline metrics. Introduces reprojective simulation and future-anchored world models, both deployed in openpilot ADAS.

Introduces RECAP (RL with Experience and Corrections via Advantage-conditioned Policies), enabling RL-style improvement for flow-matching VLAs without policy gradients. Achieves 2× throughput on complex manipulation tasks including 13-hour continuous espresso making.